In 2016 I had the opportunity to interview one of my heroes, Nancy Turner. This was a job assignment when I was working as a Gallery Manager at ArtStarts in Schools in Vancouver and we had the chance to select 20 thought leaders to celebrate the organization’s 20th anniversary with a campaign called The Next 20. I chose Nancy Turner and was lucky enough to travel from Vancouver to Victoria for this mission to ask her: what role can art and creativity play to support our next generation to thrive in the future?

On top of being one of the most remarkable ethnobotanists with an impressive, and in my opinion, precious body of work documenting plants and their Indigenous uses in the Pacific North West, she is one of the most generous and kind humans I know. She welcomed me outside of her office with a handful of Trailing Blackberries (Rubus ursinus) that she picked on campus right before our meeting and offered them to me. We walked inside her office at UVic the exact same week that she retired. As soon as I entered her office I started to recognize all the baskets that I had seen and read about in her books. It was incredible. These were celebrities to me, Nancy herself and all those baskets that she had collected throughout her career from meaningful exchanges and relationships with Indigenous knowledge keepers.

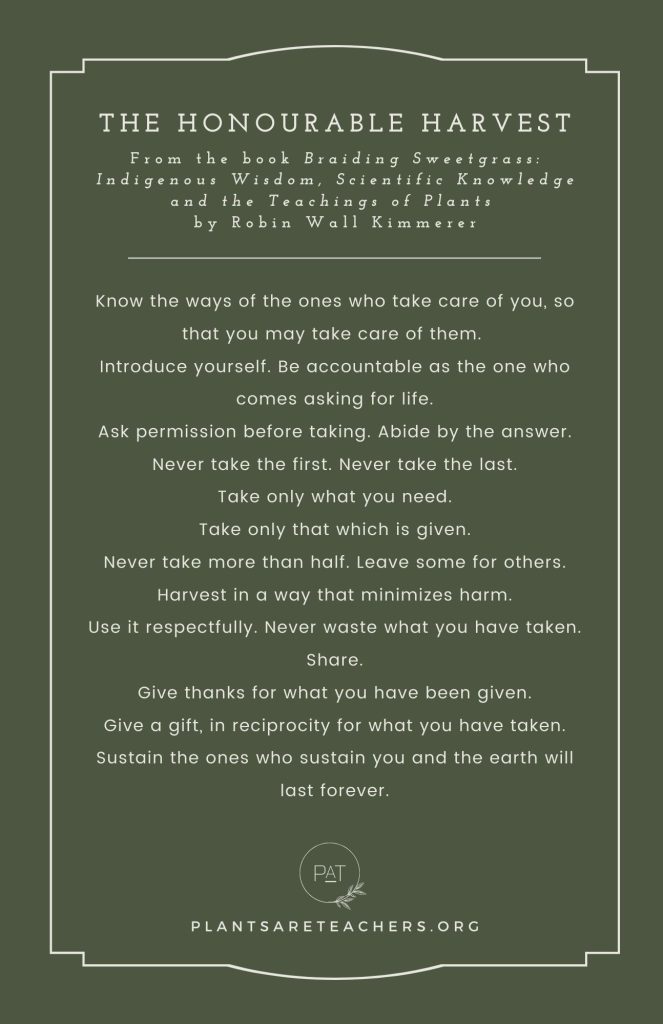

At that time I had recently read Braiding Sweetgrass, the life-changing book that has given language and has beautifully consolidated the most profound and powerful teachings. That book transformed the way I see the natural world and has provided an incredibly practical, spiritual and philosophical foundation to the work I do in so many ways.

In our conversation, I quoted the book and asked Nancy, in the context of young people suffering from “nature deficit disorder”, what she thought about “how the average person in North America knows more than 100 corporate logos and can recognize only 10 plants” . Nancy stopped and said: “Before I answer, I just want to say that Braiding Sweetgrass is the book I wish I wrote.” We both laughed. And I echo her sentiment.

The relational aspect of working with plants precedes everything else. Getting to know the place, the ecology, the people that historically have tended the land in that area, who currently do it, our presence in the land and how we impact it, the different histories and existing tensions in the territory and how everything is interconnected.

This is why for all the workshops I facilitate, and in addition to all the hands-on elements that are part of our artistic exploration with plants, I invite some reflection and sharing around participant’s own ancestral histories, relationships with the land and the different territories that have been part of their lived experience. If there have been any relationships with plants and traditional skills or hand techniques that have informed those experiences. And I also hand out little pocket cards with The Honourable Harvest. I invite you to see this short video where Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of the book, beautifully explains this teaching. You can also download the card and print it below.